Augustus Curtis showed an impetuous streak early. While most of Petersburg's free blacks intended to wait until Colston Waring returned from an exploratory trip to Liberia in 1823 before deciding about emigration, Curtis took his young wife, Minerva, and went with Waring. A 21-year-old blacksmith, Curtis was later described as a Cherokee Indian.1 In the little settlement of Monrovia, in the 1820s, he was initially part of the small elite of literate, urban and frequently mulatto settlers. But in 1831 Curtis was brought to court in Monrovia on charges of misappropriating money that belonged to a young woman for whom he was the guardian. Described as "well known to be a notorious character" by another Petersburg emigrant,2 this incident may have lost him some status among the settlement's residents. Within three years, Curtis had left Monrovia for Grand Cape Mount, then outside Liberian control, while Minerva Curtis left for British Accra.3

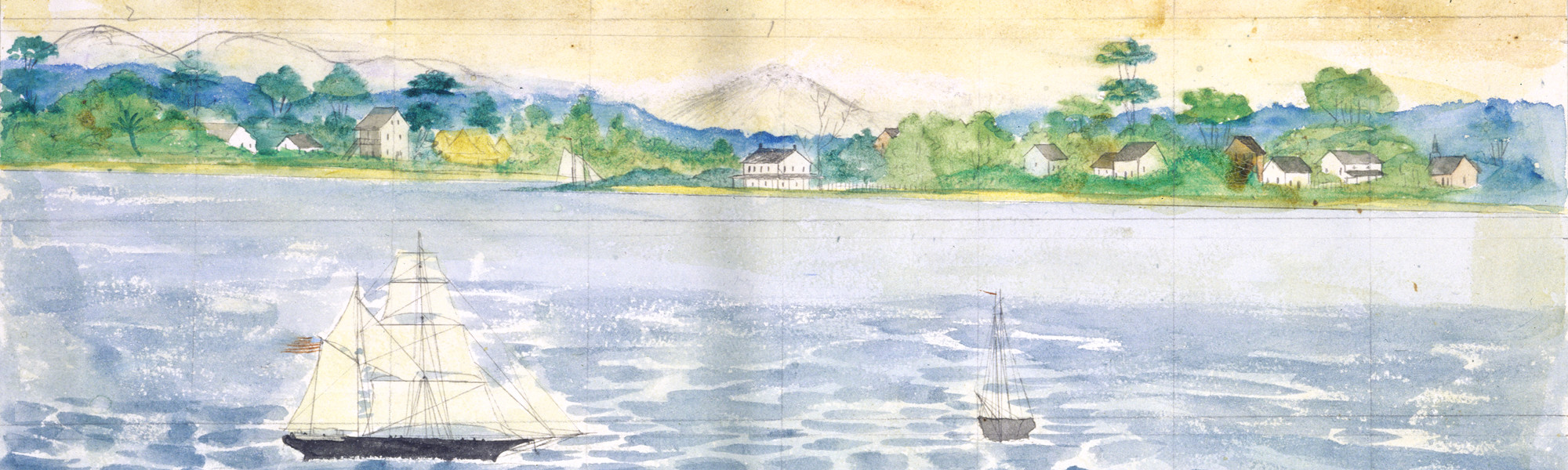

When Joseph Jenkins Roberts, Governor of the Liberian colony in 1845, felt the need to respond to accusations that the Liberian settlers had been complicit in the West African slave trade, Roberts said that he had known only one settler who became involved with that trade — Augustus Curtis.4 Curtis had moved to an area on the Atlantic coast, where the slave trade was long entrenched. Ambitious and opportunistic, Curtis was not burdened by the sense of Christian duty or Western cultural superiority that most Liberian settlers carried. This worked to his advantage once he left the American settlement. He settled among the Vai people of Grand Cape Mount and married into the family of a Gola chief, Fan Toro or Gotorrah, who controlled part of the Vai territory. By his marriage to the woman who became known as Sally Curtis or Mama Sally, he was the brother-in-law of an important war leader, Prince George Cain. At that moment in history, the slave trader Theodore Canot was attempting to leave slave trading and hired Curtis to oversee a blacksmith shop, sawpit, and ship dock at Grand Cape Mount that were part of his legitimate business effort.

There were complex intrigues at Grand Cape Mount in the 1840s and Curtis was in the middle of them. When war leader Prince George Cain went to war with Fan Toro over the extent to which the latter had relinquished sovereignty to the British, Augustus Curtis became chief advisor to Cain, while Canot aligned with Fan Toro. Canot courted British protection, but it was the Liberians who offered him citizenship in order to bolster their claim to the region. Battling the slave trade unified the American settlers as little else did and it also gave them justification for expanding their territory and their political jurisdiction.

The renegade Curtis, in aid of George Cain, reported to a British naval officer that Canot trafficked slaves outside the Vai's local system of slavery. He added as proof that hundreds of manacles were being made in the blacksmith shop. When an inspection of the shop appeared to corroborate this claim, Canot and his ship were seized and the ship taken to New York City, where both were ultimately released. Canot never returned and his settlement was burned by Fan Toro. Prince George Cain became leader of the Vai upon Fan Toro's death and, by a series of treaties and vows to end the slave trade, the Liberians became the dominant power at Grand Cape Mount.

Curtis lived out his life among the Vai. He was reportedly killed in the 1850s, but his Vai widow, Mama Sally, was an important personage in that region for some years to come, renowned among foreign visitors for regal bearing, great weight, and elaborate hairdos. As a Virginian, Native American, African American, Liberian and Vai warrior, the life of Augustus Curtis on two Atlantic coasts attracts interest not just for its high adventure, but for the links it demonstrates between all his worlds.