Harriet Graves Waring was born free in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1796 into "tolerable circumstances," as she described them. At seventeen, Harriet Graves married free black Colston Waring. They were, she remembered, "both very young, but bid fair to do well in life." Waring felt called to preach and moved his young family to Petersburg. Harriet lacked his assurance that the Lord had called him to Petersburg, but she and their children accompanied him. It was a decade in which respectable and educated free black families such as hers hoped to gain from the spread of liberty promised in the American Revolution, but they were severely disappointed by the early 1800s. One response to the increased discrimination that they experienced was to consider emigration to the American Colonization Society's colony of Liberia. Free blacks in Virginia's port cities preferred to emigrate with entire families and often in church groups.

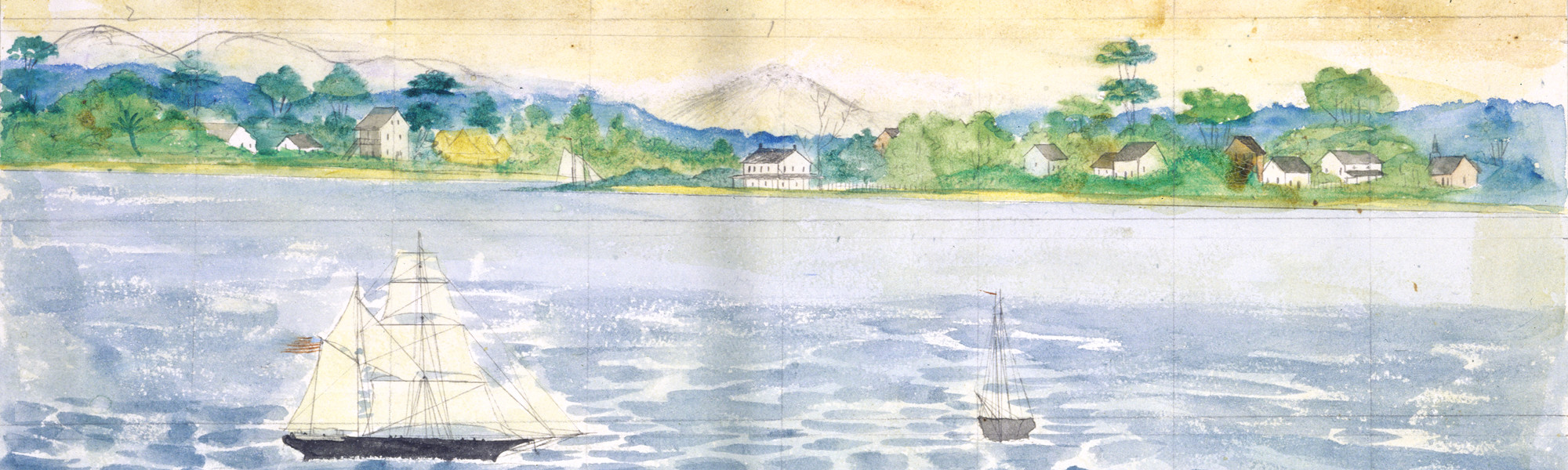

Waring, a trustee of Gillfield Baptist Church in Petersburg, was asked by free black church members "go out and make an examination of the state of the Colony [Liberia] . . . as many were anxiously desiring to know the truth respecting it." Waring's "highly favorable" report, after an 1823 trip, meant "People were daily flocking to our house." Nearly one hundred free blacks from Petersburg arranged to go to Liberia with Waring and his family in 1824. Again, Harriet Waring reluctantly accompanied her husband on a religious pilgrimage, this time with the six children born to them in the dozen years since their marriage. Once in Monrovia, the two youngest boys soon died of malarial fever. Within four years, another two children died of varied causes. In a decade in Liberia, Harriet and Colston Waring had four more children.

Colston Waring had embarked as a missionary for the African Baptist Missionary Society of Petersburg, but the Society's inability to sustain him financially meant that he had to become a commission merchant to support his family, although "he was not born a merchant, of which he was fully aware." After the death of Lott Cary in 1828 and after the Colonial Agent, Jehudi Ashmun, left the country, Waring was chosen as Vice Agent in charge and replaced Cary as pastor of Providence Baptist Church. This busy life ended in August, 1834, when Waring died and Harriet was left "a widow with four small children."1

Five years later, Harriet Waring married Nathaniel Brander, a Petersburg native who had embarked to Sierra Leone on the first American Colonization Society ship in 1820. The marriage ceremony was performed by a Norfolk native, Abraham Cheeseman who must have know the Graves and Waring families in Norfolk. By 1843, Nathaniel Brander was a Supreme Court Judge and Harriet Graves Waring Brander was a milliner. Milliner was a higher status occupation for women in America, and Mrs. Justice Brander could remain among the first families of Liberia while making and selling bonnets. They had one child, Albert Brander, Harriet's eleventh child.

Her daughters married prominent men in the Liberian colony and the African republic. The Warings' oldest child, Susanna, married John N. Lewis whose family accompanied the Warings from Petersburg in 1824. Harriet Waring Brander's other Virginia-born daughter, Jane Rose, married Joseph Jenkin Roberts, once of Norfolk and Petersburg, who was to become President of Liberia and the republic's most important statesman and ambassador.2 Reluctant to leave first Norfolk and then Virginia, Harriet Graves found herself a founding mother in a new republic.