The largest Virginia emancipation of the 1830s decade was that of Dr. Aylett Hawes of Rappahannock and Culpeper Counties. At his death, he freed over one hundred slaves for Liberia and provided money for each to be settled at Bassa Cove, Liberia, a settlement venture based on pacifist and temperance principles and designed to prove that settlers could live peacefully among the Africans and could trade successfully without dealing in rum.1 Hawes was a young man in the Revolutionary era and received a medical education in Edinburgh, Scotland. The Enlightenment science and political philosophy of his youth made him question slavery, but he spent his life among people who regarded him with suspicion for his views and he did not free his slaves until his death. Still, his efforts to moderate slavery's brutality were noted by William Grimes, a runaway who wrote of his life as a slave in Virginia. Grimes was favored to make and serve coffee in the dining room of his master's plantation. A jealous cook put an evil-tasting substance in the coffee, causing Grimes to be blamed and severely beaten. It was the master's son-in-law, Dr. Aylett Hawes, who told the master to stop beating the boy. Some years later, when Grimes ran away for the first time and was caught, it was again Hawes who drew on his aura of medical expertise to advise that the boy should not be beaten. Grimes eventually ran away successfully while Hawes' aversion to the daily cruelties of slavery was channeled into an active interest in the American Colonization Society that made his neighbors suspicious. He subscribed to the African Repository until his neighbors threatened, in 1831, to take him to court for bringing such incendiary material into the community.2

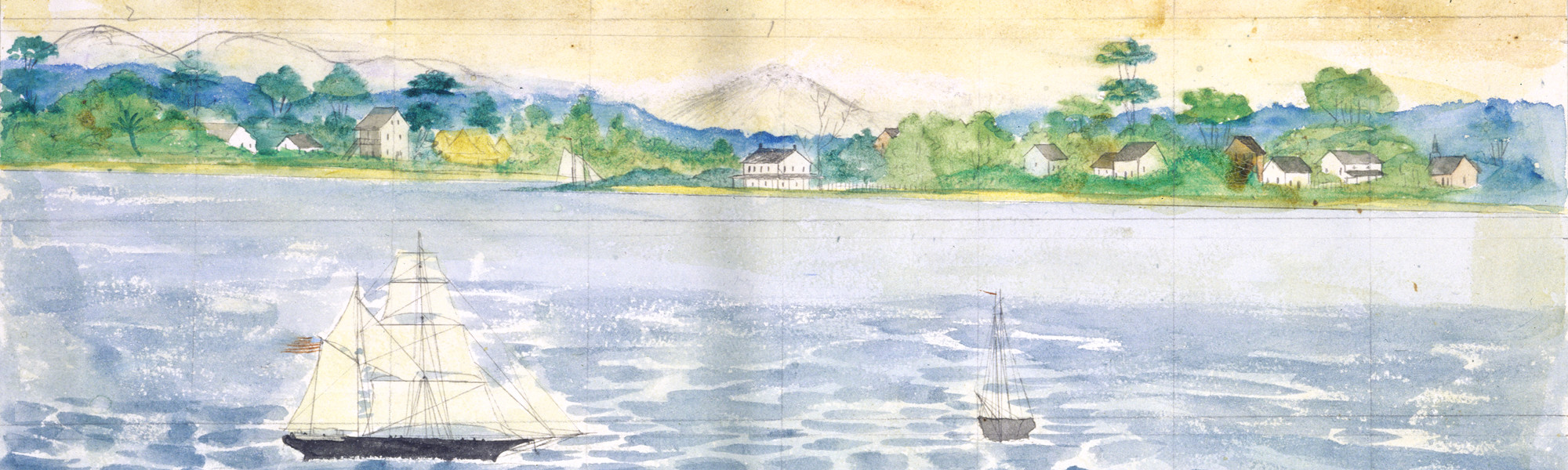

Local opinion could not prevent Hawes' will from sending approximately one hundred bondsmen to the utopian settlement. In December, 1834, they proceeded to the 700 acre tract purchased from Bassa leader, King Joe Harris. Slave traders active in Bassa country persuaded Joe Harris to destroy the settlement, telling him they could do no business with him while the Americans were so close. On the night of June 10, 1835, Bassas led by King Joe Harris attacked the settlement, set fire to the buildings and massacred twenty-two members of the emigrant party. When news of the massacre reached Monrovia, the colony's acting agent, Petersburg-born Nathaniel Brander, declared a war that lasted six months and forced King Joe Harris to promise to make restitution, to abandon the slave trade, and to submit territorial disputes to the "colonial authorities at Monrovia." This was a political and military success for the young colony, but a personal disaster for many of the emigrants and far from what Aylett Hawes had envisioned. As for William Grimes, his persistence and ultimate success in attempting escape from slavery, made his later life as a free man in the North, however limited, an enviable contrast to the sufferings of a group of people he had once known.3