Thomas Jefferson began writing Notes on the State of Virginia in 1781 as responses to queries from a French diplomat. He printed and circulated it privately in 1784, then published it widely in London in 1787. It became an important source of information for Europeans on Virginia and the United States, and since for scholars of the Early Republic. One scholar observed, “The book contains Jefferson’s most powerful indictments of slavery; it is also a foundational text of racism.” It was foundational, too, for the colonization movement, as Jefferson thought removal of freed African Americans necessary for wide-scale emancipations. The following quotations from the Notes exemplify his reasoning.

It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expence of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.—To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral. The first difference which strikes us is that of colour.

Additionally, because Roman enslavers and enslaved were both white, “Among the Romans emancipation required but one effort. The slave, when made free, might mix with, without staining the blood of his master. But with us a second is necessary, unknown to history. When freed, he is to be removed beyond the reach of mixture." Jefferson was well aware of the prevalence of such “mixtures,” not uncommonly instigated by enslavers such as he.

Jefferson's words on freedom and equality in the Declaration of Independence earned him recognition as a visionary for the ages. Despite evident contradictions, however, his thoughts on who was included in that vision were narrowly limited by the conventions of his time. He saw a world dominated by white men, but near the time of his death in 1826 he observed that “all eyes are opened, or opening to the rights of man.” Jefferson's written words had a tremendous effect on the formation of the Republic and both the pro- and antislavery movements. Jefferson justified both slavery and removal by charging people of African descent with inferiority, dismissing evidence of Black genius such as Phillis Wheatley's poetry and Benjamin Banneker's almanac. Racial prejudice such as Jefferson feared and embodied was strong and assumed immutable.

After the Revolution many Americans hoped that slavery would end due to moral suasion and lack of economic benefit; it was ended, or put on a path to end, in New England and the Middle States. But in the South, it only strengthened and grew after the invention of the cotton gin made it more profitable and opened up the lower South to massive cotton production.

Many people were aware of the contradiction of slavery in a nation based upon freedom, but ending it presented the issue of incorporating or excluding Black people from the polity—both felt risky to white people who preferred to maintain their social, political, and economic supremacy. They increasingly saw free Blacks as threatening the status quo. A Virginia law enacted in 1782 allowed manumissions, but prejudice and concerns over the growing number of free Blacks resulted in an 1806 law that required newly freed people to leave the state within a year. The successful Haitian Revolution in 1791 and Gabriel's planned rebellion in Richmond in 1800 heightened white fears of violent revolt. The Virginia Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, founded in Richmond in 1790 by Quaker emancipator and abolitionist Robert Pleasants, could not continue in that climate. About forty percent of Virginia's population was enslaved in 1810, and the small number of free Blacks was rapidly growing.

A coalition of Upper South politicians and Northern and Southern ministers offered a solution to the dilemma in December 1816 when they established the American Colonization Society (ACS). They planned to establish a colony on the west coast of Africa for free Blacks who were willing to emigrate. There they could enjoy freedom without the prejudice and limitations imposed upon them in the United States. The colony would encourage manumissions and many hoped it would help to gradually end slavery. At the same time, it would reduce the free Black population, thereby tempering opposition and even gaining some support from proslavery activists. A colony would further help end the Atlantic slave trade that continued illegally despite President Jefferson and Congress banning it as soon as the Constitution allowed, on January 1, 1808. Colonization would bring western civilization, commerce, and Christianity to Africa. Evangelical supporters even hoped that the initiative might redeem the nation for the sin of slaveholding.

From the outset, colonizationists appealed to Thomas Jefferson to formally support the organization but he declined. Other Virginia presidents, James Madison, James Monroe, and John Tyler, were actively involved, but none of these men released individuals from slavery for freedom in Liberia. More than two-hundred Virginians did, however.

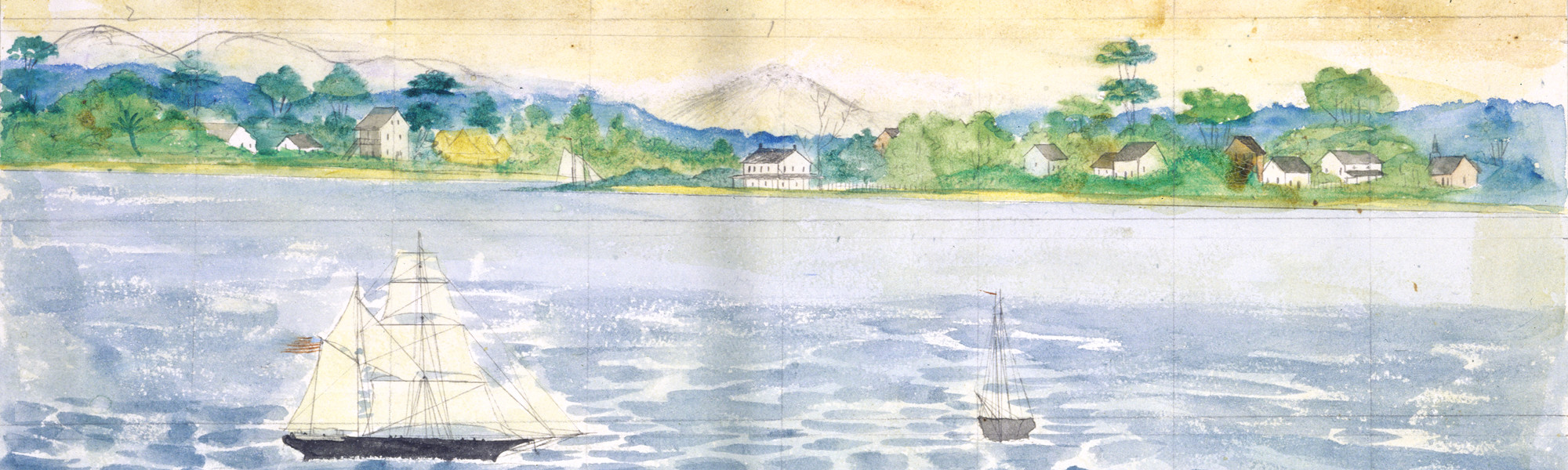

Northern free Blacks largely opposed colonization but it appealed to many in Virginia, especially in the early years. Free Black Virginia emigrants were among the colony of Liberia's leaders in business, religion, education, and government. In 1847 Liberians established the first independent republic in Africa and elected Joseph Jenkins Roberts, originally from Norfolk and Petersburg, its first president. By 1866 almost 4,000 Black Virginians emigrated, some only because it was a condition for freedom. Given the opportunity to go to Liberia, however, the vast majority of African Americans in Virginia, as elsewhere, refused. They were daunted by the high mortality rate from tropical diseases and, most of all, preferred to stay in the land of more immediate ancestors, in the communities and nation they knew and helped build.

Back in the early American Republic, as the nation grew, so did controversy over slavery, resulting in the Missouri Compromise of 1820. When Thomas Jefferson heard of the controversial deal that extended slavery to Missouri but restricted slavery in new states to the north, it was as a “a fire bell in the night” that filled him “with terror.” He likened slavery to having “the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” To many white people, colonization—impractical though it was—seemed like the only potentially viable response. Local ACS auxiliaries sprang up in the North and South and colonization in the 1820s became the first national antislavery movement.

In 1829, David Walker of Boston published his Appeal...to the Coloured Citizens of the World. He powerfully and extensively critiqued Thomas Jefferson's racial views from Notes on the State of Virginia. Walker also denounced colonization and articulated African Americans' case for inclusion. He followed his conclusion with Jefferson's familiar words from the Declaration of Independence including these lesser known ones: “But when a long train of abuses and usurpation, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.” Heavily influenced by Walker, William Lloyd Garrison advanced the cause of emancipation in The Liberator and Thoughts on African Colonization, thereby launching the Abolition movement for immediate, unconditional, general emancipation. Colonization along with Jefferson's writings, both positive and negative, proved a potent catalyst for this evolution.

During the 1830s, support for the American Colonization Society fell away in New England and the lower South, while remaining significant in the Mid-Atlantic states, especially Maryland and Virginia. By 1867, more than 13,000 people emigrated from the United States to Liberia, more from Virginia than any other state.

The Records of the American Colonization Society and other sources on this website show various Black and white Virginians actively wrestling with the contradictions between freedom and slavery in their lives and in the nation. The ideals on which the nation was founded have yet to be fully realized and contradictions still exist. The evolution continues and Thomas Jefferson's words and life continue to incite passion and inspire activism for varied goals.