Ann Randolph Page was among the most benevolent of colonizationist emancipators, and the people she freed — most members of an extended family with the same Page surname — were among the most prepared of the newly emancipated emigrants. Some of the adults could read and write, many of the men practiced trades in addition to farming, and the women had learned a variety of domestic skills. Most, too, had embraced Christianity. The black and white families exchanged letters across the Atlantic for over a decade. The Liberians expressed longing to see family and friends of both races in Virginia and complained about high prices and difficulties in obtaining needed goods, but expressed overall satisfaction with their new home in Africa.

Although her family held slaves, when Ann Randolph Page was growing up in Frederick County, Virginia, her pious Christian mother used to warn her that "your guests see your well-spread table, but God sees in the negro cabin." Perhaps such sentiments help explain why, not long after eighteen-year-old Ann married one of the wealthiest slaveholders in Frederick County, Virginia, she fell into a deep depression. Unlike her mother, however, she realized that slavery itself violated the core teaching of Christianity, to "do unto others as you would have them do unto you." But Ann felt helpless to bring about substantive change. When in 1816 she heard of the plan to establish the American Colonization Society it seemed like a candle in the darkness. She spent the rest of her life supporting the organization, mentoring white men who served as managers and agents, and preparing potential emigrants among the enslaved people at Annfield. While her initiative met with considerable success and the emigrants expressed overall satisfaction with their new home in Africa, the endeavor fell far short of the utopian vision that inspired her and others.1

Some of the enslaved men and women embraced the religious teachings and the educational opportunities she offered and received preferential treatment in return. Through apprenticeships, men learned trades such as shoemaking and blacksmithing, in addition to farming skills. William Page apprenticed as a wheelwright, but found shoemaking more to his liking. Robert Page mastered blacksmithing. Because they worked in and around the manor house, the women learned a variety of domestic skills. In the decade before their departure, Ann Page amassed provisions to help sustain the emigrants for a year. She also mentored a young tutor from New England, Charles Wesley Andrews, who became an Episcopal Minister, an agent for the Virginia Colonization Society, and her son-in-law when he married her daughter Sarah.2

Ann Page wrote to Ralph Gurley, secretary of the American Colonization Society, and told him how she persuaded her enslaved people to emigrate. She told them she did not think that "white people" in the United States would allow them to be independent — "to continue together must be to continue in bondage." Reluctant to give up her own oversight, she explained that "I cannot set you free here, you would be in obscure places where I should never know whether you were doing good or ill." Rather, she told them, "I yearn to have you in a situation where your children cannot be sold from you … your children will receive education there — and … in walking in the paths of [God's] commandments … you will be as a light set on a hill."3

Ann Page died shortly after the last departure of emigrants from Annfield to Liberia, but some of them corresponded with Charles and Sarah Andrews. The letters illuminate life in Liberia and Virginia and personal relationships among people on both sides of the Atlantic.

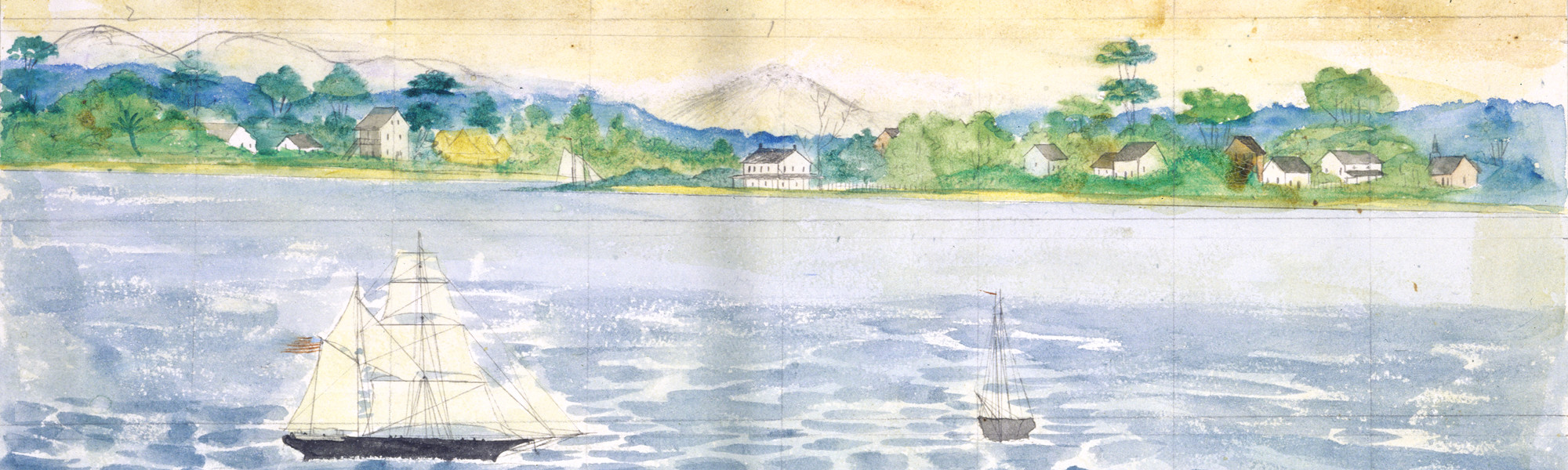

The first group of emigrants from Annfield sailed aboard the America in 1832. Almost half comprised one family: Gilbert and Mary Page, ages 37 and 34, with their children Ampha (16), Jane (7), Thomas (6), Robert (5), and John (1). With them was Catharine Wilson (52), the oldest of all the Annfield emigrants and probably Mary's mother. Other Pages included Daniel (32), William (26), Sarah (21), Winney (21), Ann (8), Jane (3) and Lucretia (2).

Their experiences in Africa were mixed. The 1843 Liberian census noted that Daniel Page died in 1841 of diseased lungs. In 1847 his sister Peggue Potter informed Charles and Sarah Andrews of his death, and said that he left three children — two girls and a boy — behind. Catharine Wilson and Gilbert's wife Mary Page both died in 1842 of unknown causes. In 1843, Gilbert Page (50) worked as a laborer; the children were mostly grown and earning wages themselves, though they still shared their father's household in Monrovia. Ampy (22), Thomas (19), and Robert (18) were also laborers, although Ampy was also described as an invalid. Jane (20) was a washerwoman, Lucy (possibly Lucretia) was a nurse. John was not mentioned. Last in the household was two-year-old Susan — if she was Mary's child it is likely that she never recovered from the pregnancy and birth. William Page worked as a shoemaker, although leather was very dear in Liberia. He was the head of a household of seven, but this family did not appear in the census.4

The second Annfield contingent sailed on the Ninus in 1834. Susan (18) and Daniel (5) Page's names appear first on the ship's roll. Further down are Robert M. and Matilda (20), with their two young boys, John (3) and William (2). Another son, Robert, was born in Liberia. They do not appear in the census, but Robert senior sent a letter to Charles and Sarah Andrews in 1839 and two in 1849. In the first he expressed gratitude for their correspondence and reported that "Africa is a new country with some inconveniences, yet we enjoy many blessed privileges. We have to work hard, but we get a tolerble comfortable support." He was proud of his sons' achievements in the mission school and the Baptist Church in Edina. Other records show he became a deacon at the church the same year. Robert Page farmed and worked as a blacksmith, but a fire in his shop forced him borrow money for a new bellows. He asked for assistance in funds or in scarce goods such as steel, leather, and cloth. He reported that his brother Thomas had professed Christianity and was working on a ship as a cooper while his children lived with Robert.5

In 1849, Robert Page wrote Charles Andrews and shipped him seventy-three pounds of coffee he raised himself. He asked Charles to give four to his (Robert's) mother, and requested that he send to Liberia a little flour, molasses, and bacon as well as a few yards of alpaca cloth. He also asked "to learn their true ages as somehow we have lost the acct." He told of the wife he married in Liberia and the five children they had added to their family, and he closed by saying that "The children all join me in love to the Grandmother they have never seen … give our love and respects to your family and all enquiring friends."6

Another family also emigrated to Liberia in the 1830s, but their names do not appear on an ACS ship's list. Thomas and Becky Page sailed with their children Solomon and Peter Page and Thomas and John Parker. Apparently Becky died because Thomas remarried by 1843 and the couple had an infant daughter. Solomon does not appear with them, but the rest of the family enjoyed good health. By 1849, however, Thomas's health had suffered but he still farmed in Edina, Liberia. His two sons Peter and Solomon lived away and worked primarily as teacher's assistants in a mission school, but they still helped their father on the farm. He praised his second wife Elizabeth as a good stepmother and industrious housekeeper.7

In 1836 one last group of three departed Annfield on the Luna. Peggue Potter (23), the sister of Daniel and Winney who sailed in 1832, took her son Daniel William (2). Ruth Lightfoot (44) was the second oldest emigrant and was probably Peggue Potter's mother. When Peggue wrote Charles Andrews in 1847 she said that "any man can live heare that will Work and if a man is got money he can live[.] all the Fault I find in this Place the things is so deare that I has to work to get something for me and my children to Eat and as fast as I can get a little money I have to take it all the Buey [buy] some Cloths for my Children to ware." The family, including Peggue's mother, was "living in a Tach hut," a common dwelling made of bamboo poles covered with mud or vegetation and a thatch roof. She dreamed of living in a frame house someday.8

The last extant letter is a copy of one that Sarah Andrews wrote to "My dear Young friends John, Peter, and Solomon. She was writing in response to letters that each had written to her, even though they were children when they left Annfield. She wrote that "you do not know how much gratified I am to hear such good accounts of you & to know that you are all trying to get a good education, and especially that Peter has become pious — for I loved you & your Parents before you — your mothers were my playmates when a child, and my kind and affectionate friends always. I remember well the countenance of each of you and how much delight I used to take in your little ways and words when you were little children." She answered their requests for knowledge of their birthdates as best she could, and told them that "Aunt Milly (probably the sister of their fathers Thomas and John senior), who lives with us talks most lovingly of you all; especially her little Peter."9

With the affectionate closing of this letter, probably written in 1850, the historical record falls silent. Like her daughter, Ann Page would have been pleased with the continued connections to the family in Virginia, to education and religion. While Liberia did not become as light on a hill, the emigrants she sponsored contributed positively to the well being of their family, community, and the early development of the nation.