No family was more associated with the creation of the republic of Liberia than the Roberts family of Norfolk and later Petersburg, Virginia.

JOSEPH JENKINS ROBERTS and two of his brothers, HENRY and JOHN, were the dominant men in politics, medicine, and Methodism as the colony of Liberia became a republic and made policy decisions that would reverberate through generations. Henry Roberts, initially a trader, returned to the United States for a medical education and practiced in Liberia. John W. Roberts became bishop of the Liberia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. But Joseph Jenkins Roberts, in particular, became the symbol of the new Liberian republic. He was the first African American governor of Liberia for six years before ascending to the presidency when Liberia became a republic in 1847. Those who believed that Liberia was a symbol of African American capacity to govern a republic, to expand their commercial skills, and to spread Christianity and education, held Roberts up as an example of black achievement. Those who believed that the early leaders of Liberia were a privileged mulatto class who looked down on other emigrants and especially on the African groups living in the region, saw Roberts as an almost-white man too comfortable with white American values and unfit to govern in Africa. The image of Roberts has been manipulated for more than 150 years to prove one point or the other, usually in the service of an argument over the meaning of race and nationality in America and in Liberia.

The Roberts family consisted of two households when they left Norfolk, Virginia for Liberia on the ship HARRIET in March, 1829. AMELIA ROBERTS (1789-1834?) and five of her seven children made up one household and her second son, JOSEPH JENKINS ROBERTS (1809-1876), with his wife SARAH and an infant child who died in that year made up a second household. They took with them a long history in Virginia that had shaped their values and their goals. Amelia Roberts was reportedly born in Mathews County, Virginia and one account has her receiving her freedom in 1804, at age fifteen.1 Mathews County was part of the 1600s Tidewater settlement pattern, when the system of English plantations and the forced labor of Africans was still evolving. She and her ancestors faced the Atlantic Ocean. Rivers, bays, boating, transatlantic commerce, and foreign sailors were parts of this world as was the uneven but inexorable growth of the institution of black bondage in 1600s Virginia.

Seventeenth and eighteenth century relationships between European indentures, enslaved and free Indians, and Africans whose indentures were lengthening into permanent and hereditary bondage produced many mulattoes in the Tidewater area and Amelia Roberts is frequently described as a light mulatto.2 Her first child, Uriah, may have been born in 1807 and her second, Joseph Jenkins Roberts, was born March 15, 1809 in Norfolk. Her name at birth and the name of the white father of at least some of her children born between 1807 and 1821 is not known, but all of her children except John Wright -- Uriah, Joseph, Elizabeth, William, Henry and Mary -- bore the middle name of Jenkins3.

In Norfolk, Amelia married James Roberts, a free black boatman who carried goods and engaged in commerce between Petersburg, where they soon moved, and the Norfolk wharves. The free black population of the Chesapeake area grew rapidly in the decades after the American Revolution, mostly from manumissions, but some from self-purchase. Prior to 1840, only a few of them in the upper south — perhaps one hundred families — acquired more than $2000 worth of real estate. Those few who did acquire some significant property were most often mulattoes who, at some stage, had received educational or financial assistance from white relatives. But they would not have been able to maintain their advantages without an understanding of trade and a willingness to take risks to expand their businesses. James Roberts was a successful businessman and his oldest stepsons learned the trade from him4 and received basic instruction in reading and writing, perhaps from such men as Joseph Shiphard who organized free black schools in several cities and was also an emigrant to Liberia on the Harriet.

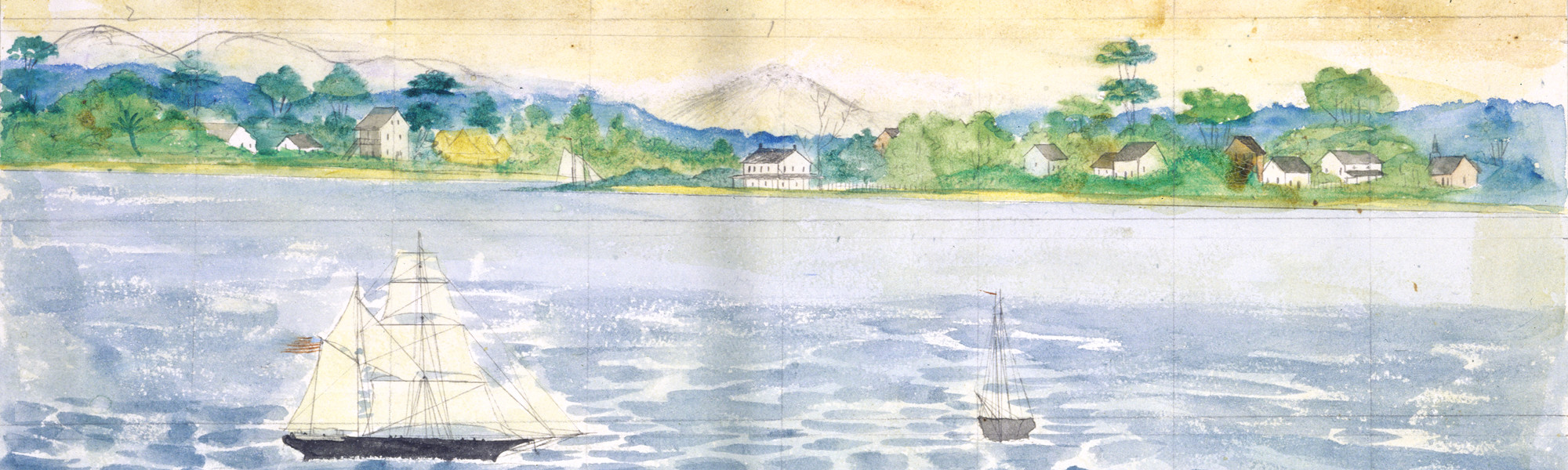

Petersburg was a busy riverport city in the early 1800s, with a high percentage of free blacks in its diverse population which included refugees from the black revolution in Santo Domingo (Haiti), Quakers, and tobacco factors from Britain. Free black Baptist and Methodist congregations thrived and most Protestant denominations had active black members, both free and enslaved. Petersburg Baptists organized an African American Missionary Society and were connected with a similar Society at Richmond's First Baptist Church. Attempts to settle free blacks in West Africa reached Petersburg swiftly, as did the formation of the African Colonization Society. Petersburg Baptist minister Colston Waring led one hundred of Petersburg's free blacks to Liberia in 1824. Five years later, another group that included the Roberts family left Petersburg. Evidence suggests that it was primarily the lack of liberties and citizenship in Virginia and the American nation that led Joseph Jenkins Roberts to persuade all but his older brother to emigrate. James Roberts had died, leaving them considerable property. Joseph Roberts formed a trading partnership with William Colson, a black Petersburg barber. Colson would ship basic supplies to Liberia while Roberts would ship ivory, camwood, palm products and other trade goods from the Liberian interior to their trade partners in Philadelphia.

The ambitious young American lost his first wife and infant child in his first year in Monrovia, the main city of Liberia. He later married Jane Rose Waring, the daughter of Colston Waring. Arriving ten years after the first settlers, Joseph Roberts did not take part in what came to be thought of as the "pioneer" era of Liberian history which featured frequent conflicts between the ACS and the settlers. By the time of his arrival, settlers had gained more political power and Roberts distinguished himself in 1833 by becoming high sheriff whose chief duty was to collect taxes. He took part in the continuing militia forays into territory held by groups in active opposition to the American settlement. Although the white-dominated American Colonization Society had envisioned a nation of farmers and missionaries, trade was clearly the only source of money in Liberia, as in other colonial settlements. Roberts was more than prepared for this. Throughout the 1830s, Roberts expanded his trade and sent his brother back to medical school.

When a new constitution was written in 1838, Roberts was appointed Lieutenant Governor and, following the death of the ACS-appointed white Governor in 1840, Roberts became the first African American Governor of Liberia. He held this post from 1842 until 1847. Liberian independence from the American Colonization Society was hastened by the fact that Britain and France, with their colonies of Sierra Leone (BR) and Ivory Coast (FR) so near to Liberia, did not see that country as anything more than a private venture, unsupported by the United States government. This was essentially true. In order to regulate trade, negotiate boundaries, or conduct diplomacy, Liberia needed status as a nation. A constitutional convention produced a BILL OF RIGHTS and CONSTITUTION modeled on that of the United States. Roberts became the first President of the new Republic of Liberia, a position he held from 1848 until 1856.

It was in 1844, during his period as Governor, that he first returned to the United States and, over the next 25 years, he traveled frequently to the United States and England in efforts to raise funds for Liberia, get diplomatic recognition, or encourage emigration. As President, his greatest concerns were the recognition of Liberian sovereignty, territorial expansion, and suppression of the slave trade. He saw the first two as central to the third. He was also concerned with the advancement of education in Liberia and, in his several trips to the United States, he always sought funds to establish or maintain schools. Roberts became president of the University of Liberia in 1861 and remained in that position for almost ten years, a decade culminated by what must have been a triumphal return to the United States and to Petersburg in 1869. He was the ex-President of an African Republic and slavery was ended in the United States.

In that happy moment, he gave his views of the meaning of Liberia,5 equating its settlement with that of Jamestown. While his comments are somewhat tailored to a white audience of potential donors and frequently rely on comparisons between the European settlement of North America and the African American settlement of West Africa, he is clear and outspoken about the goals sought in creating Liberia. Most important was as a refuge for persecuted free blacks and next in importance was the need to demonstrate African American capacities and capabilities in government, commerce and culture. It was to be an outpost for Christian missions and for Western civilization generally, but the first two were Roberts' primary impulses toward African settlement.

Then a great upheaval in Liberian politics brought him back into the presidency. That upheaval was a signal of problems to come. Liberian politics had divided into factions. An upriver faction of farmers combined with recent emigrants from the West Indies resented the dominance of the Monrovia-based merchants organized as the Republican Party. A bitter verbal battle between the Republicans and the True Whig Party led to an election overthrow of Roberts' group, the Republicans. But when their man, President Roye, attempted to give himself another term without an election, he was removed from office. This was coupled with a disastrous loan that the government made with Britain that would be impossible to repay and Roberts was called upon in 1871 to serve again and to attempt to change the terms of the British loan. Roberts failed to persuade the British to modify the interest rate or change the loan and debt became a permanent drain on the Liberian economy. He remained in public office until 1874 and died in March of 1876. In his will, he left $10,000 and a rubber farm for education.

Roberts deserves a well-researched biography that places this complex man in Virginia, in Africa, in London, Washington, and Saratoga Springs. In his many representations for Liberia over decades and in his own self-fashionings, Roberts remained true to an initial set of values that reflected those of the early American republic in which he had grown up. He was a small businessman, an evangelical Protestant, a believer in education, and a citizen of a republic.