The family connections between Virginia free and emancipated blacks emigrating to Liberia are frequent and layered. The life of Desserline Harris, free black emigrant from Alexandria to Liberia, serves as an example. The Harris family in Alexandria, father John Harris and children, Desserline and Bathsheba, were property owners and soap makers After the city of Alexandria left the District of Columbia and reverted to the state of Virginia in 1846, John Harris and daughter Bathsheba moved to Washington City while Desserline Harris emigrated to Liberia in 1848. Although he encouraged his father and sister to follow and they made tentative inquiries, there is no record of their leaving the United States.1

But his Harris and Henry cousins in the Shenandoah Valley showed more interest. How the Henry and Harris families are related is not clear, but they were able to keep track of their connection through migrations from the Tidewater to the Shenandoah Valley and to Alexandria. Patrick, Williamson, Dunkin and John V. Henry began as slaves in Westmoreland County, owned by Martin Tapscott, who freed their mother Lavinia and Williamson and intended to free Patrick, but died suddenly. Patrick purchased his freedom and somehow the other two brothers were freed. All four moved to Rockbridge County in the Shenandoah Valley. While Williamson and Dunkin (now Duncan) had modest amounts of property, Patrick and John V. acquired valuable positions. Thomas Jefferson hired Patrick Henry to be caretaker of Natural Bridge, a scenic rock natural wonder that Jefferson then owned. John V. Henry was employed to work on the buildings and grounds of Washington College with Samuel Harris, apparently a cousin.2

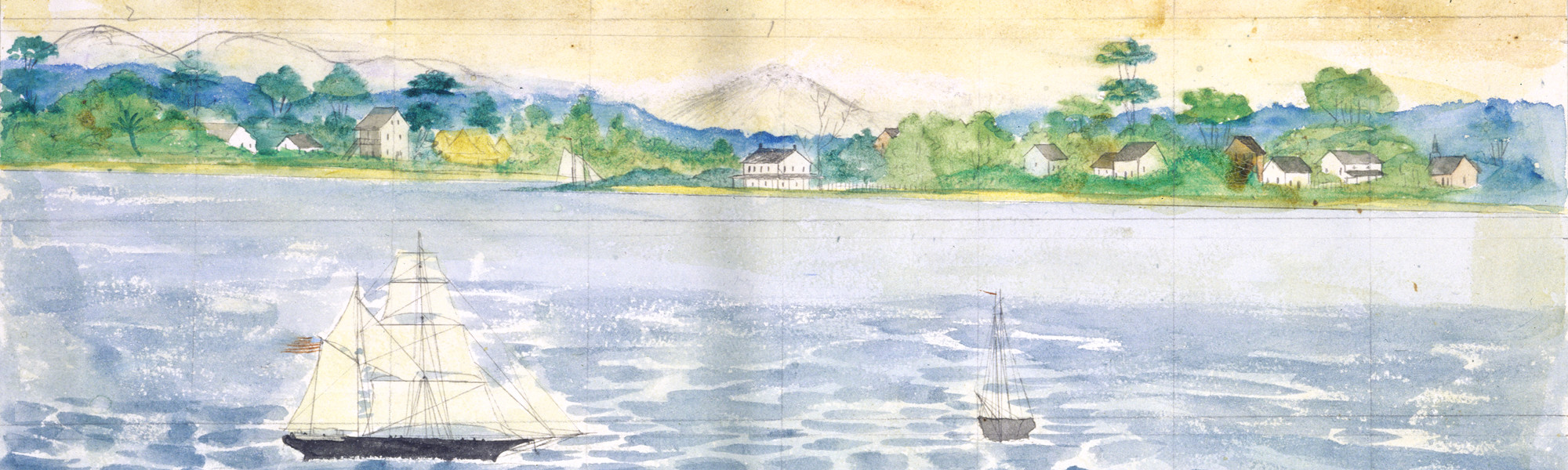

In 1849, the family of Samuel Harris, freed by a professor at Washington College in Lexington, was sent to Liberia as a bellwether for the region. If free blacks and emancipated slaves in Rockbridge County heard nothing bad in a year, they would migrate. To the consternation of local auxiliary officers, Harris wrote back that he and his family were having a very hard time. Colonizationists were furious and described him as "whining" and "babyish." It appeared that free blacks from the Shenandoah Valley would not volunteer again to go to Liberia. But letters from Desserline Harris, now the acting Secretary of State in the Liberian Republic, encouraged his uncle, John V. Henry of Lexington, to accompany Diego Evans, leader of a subsequent group from that region. John V. Henry sold his house and possessions and brought his family to Liberia with Evans in 1849. The prospective emigrants organized and left Rockbridge County in late 1850.3

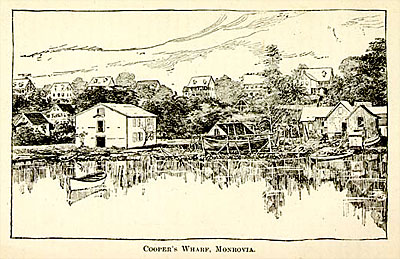

Upon their arrival, Henry, his son, Patrick Henry, and his nephew, Desserline T. Harris, started a mercantile firm, perhaps hoping to capitalize on their connections to the port of Alexandria. Harris announced that "John V. Henry and Company… will import and sell — I will say, most everything."4 But John V. Henry did not survive long and Desserline Harris, the ambitious and optimistic young entrepreneur from Alexandria, also died after several highly successful years in Liberia. The history of this family is murky in a manner similar to that of other relatively prosperous Virginia free blacks with white male patronage. What is known of their family networks raises more questions about their histories than it answers.