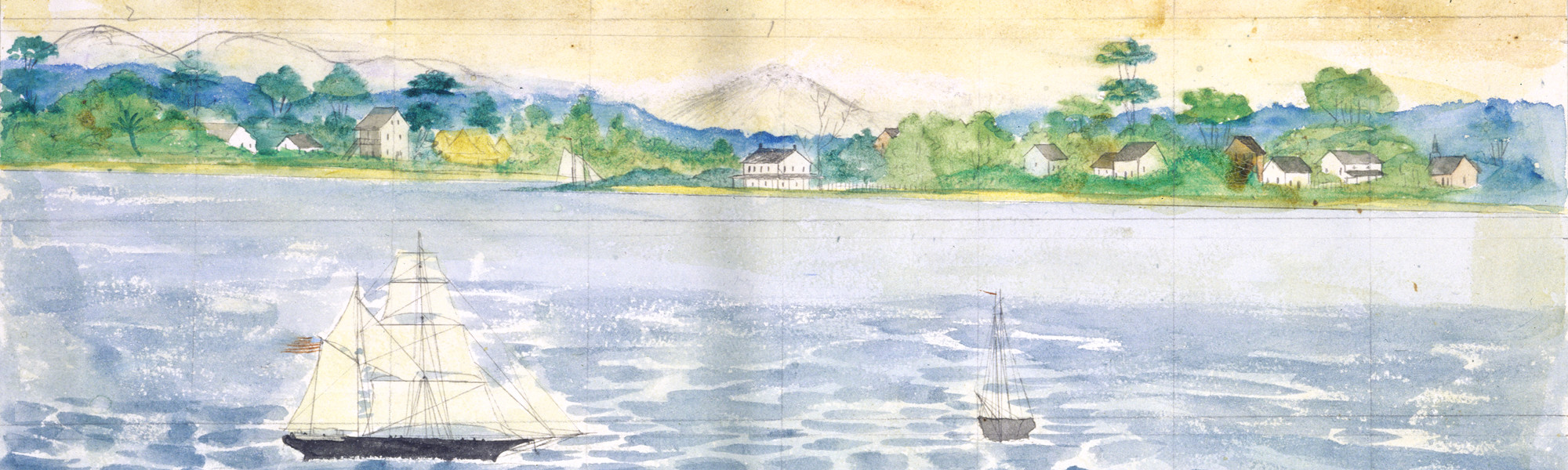

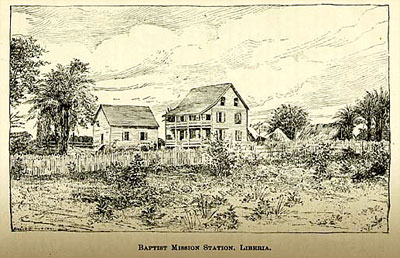

African Americans in Liberia were frequently called "white men" by the West Africans whom they encountered. This was partly because many of them were mulatto, but also because they brought nineteenth-century American values to Africa with them. Many settlers seldom ventured far from the coastal towns and river settlements unless leading a militia force. African American missionaries, however, moved to be near the groups they hoped to convert to Christianity, and John Day, Jr. was remarkable among these, both for his dedication to the people of Grand Bassa and the story of his origins in Virginia. Day took himself to Grand Bassa to work closely among the Africans as a teacher and missionary for both the American and Southern Baptist Conventions. His decades among the Bassa increased his appreciation for them. Although he served in governmental positions, including a Supreme Court appointment, his chief work was with the Bassa people. Day set up a school called Day's Hope at Bexley.

John Day, Jr., a Baptist minister, was born in Hicks Ford [now Emporia], Virginia, in 1797 into a family of free blacks. The Days had a family story, perhaps embellished, that was a variant on the many multiracial unions that created Virginia's early free mulatto class. He described his father as "the illegitimate grandson of an R. Day of S. Carolina whose daughter humbled herself to her coach driver" and was sent to Virginia to have the child. He noted that the woman left money for the child's education. Day added, "My mother [Mourning Stewart] was the daughter of a colored man of Dinwiddie County Virginia whose name was Thomas Stewart, a medical doctor, but whence he obtained his education in that profession, I know not."1 John Day's grandfather, Thomas Stewart, owned a large Dinwiddie County plantation. In his will, he freed at least 17 slaves [see http://www.usu.edu/history/faculty/nicholls/manumissions]. But the 17th and 18th century Virginia that gave rise to such mixed families began to end even before the Revolution as enslaved Africans lost legal status compared to indentured whites.

The elder John Day, a skilled cabinetmaker, saw his status decline and he fell back among the common lot of free blacks. The father took to drink, lost his business and property and left the state. He left behind John Day, Jr., who had been schooled and socialized with his white age mates, to work off his father's debts. A brother, Thomas Day, became a legendary cabinetmaker in North Carolina, and John Day, Jr., became a Baptist minister. He felt his calling to be a missionary in Haiti. But he received little or no support from Virginia Baptists in this endeavor and turned his attention to Liberia, leaving Hicks Ford, Virginia for that colony in 1830. His wife, Polly Wickham, and their four children died soon after the family arrived in Liberia. A generation later, in 1854, he wrote an open letter to free blacks in America saying, "I have noticed the prohibitory and oppressive laws enacted in many of the states in regard to you, I have wept and wondered whether every manly aspiration of soul had been crushed in the colored man, or does he pander to the notion that he belongs to an inferior race?"2 Until his death, John Day continued to believe that Liberia offered more opportunity for free black families than did the United States, and that one of those opportunities was for Christianizing Africa.