Historians have worked to reconstruct the thoughts and actions that drove the colonization movement into the center of debates over slavery and race in antebellum America. To do so, they have consulted written documents produced by the American Colonization Society, such as ship registries, correspondence and literary "sketches." Along with textual output, the Society used paintings, photographs, and prints to demonstrate the efficacy of their work and garner support for their mission. Visual imagery is as useful as textual documentation in deepening our understanding of the cultural underpinnings and propaganda strategies of the American Colonization Society. Far from being straightforward images, artistic compositions are actually informed by a web of visual and cultural associations formed in nineteenth-century American popular visual culture. Colonization pictures draw on notions of race, slavery, and civilization to create an image of Liberia that would appeal to an American audience. By focusing on three pictures created with the cooperation of Virginians, this essay explores how colonization imagery was shaped by black settler and white colonizationists' cultural beliefs and how the American Colonization Society used visual imagery as a tool of persuasion to promote the colonization movement in antebellum America.

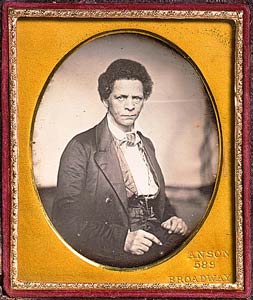

One source of visual imagery the ACS had at their disposal were photographs by African-American daguerreotypist and émigré to Liberia Augustus Washington (b. ca. 1820 - d. 1875).1 Once the operator of a successful daguerreotype studio in Hartford, Connecticut, Washington continued to ply his trade after he settled in Monrovia, Liberia in late 1853. In addition to local patronage in Monrovia, colonizationists in the United States were eager to obtain photographs from Liberia. Among the first photographs by Washington sent back to the United States were portraits of Virginia natives, Joseph Jenkins Roberts and Jane Roberts. Today, the whereabouts of these portraits is unknown; but, archival research has shown that the daguerreotypes of the couple by New York photographer Rufus Anson are most likely copies of Washington's original daguerreotypes.2 When Washington's portraits reached the United States, they were warmly praised by the Philadelphia newspaper the Public Ledger. The article proclaimed, "Science and Art are taking hold in long benighted Africa. The Liberian Republic is gradually and permanently spreading its powerful influence for good."3 The phrase "science and art," a reference to the technological and aesthetic applications of the camera, implies these photographs from Liberia were seen as symptomatic of the march of civilization into Africa.

Washington and his sitters worked to produce portraits they most likely knew would have an American audience. As Liberia's first president, Roberts' intense gaze beams out from under a slightly lowered brow and closed fists rest on his lap but do not entirely relax. First Lady Jane Roberts inhabits a more plaintive pose. A languid gaze is matched with sloping shoulders and slightly hunched back. Her hands, in lace gloves, rest on her lap while gently curled fingers cradle a fan. Both sitters posed in three-quarter view. Like many Americans, the President and First Lady of Liberia marshaled pose, dress and countenance to convey identity, construct self according to bourgeois criteria and "like many blacks in America" relished the opportunity to have one's portrait taken absent of racist distortion. By presenting themselves as respectable middle-class subjects, the Robertses refuted negative stereotypes that pervaded the portrayal of African-Americans in nineteenth century visual culture, such as those found on sheet music. 4

As portraits from Liberia, the daguerreotypes also signified in a specifically Liberian context. For example, clothes were a particularly loaded way of signaling one's place in Liberian society. Jane Roberts took her seat before Washington's camera dressed in fashionable clothes distinctive to women's attire in the United States in the 1850's: a front-fastening jacket bodice with v-neck, long sleeves with ruffle embellishment, underlying chemisette and full skirt.5 Joseph Roberts also wore dapper haberdashery. As anthropologist Svend Holsoe writes, "For official functions, top hats and tails were de rigueur, no matter that they were hardly appropriate in ninety-degree weather with an equally high humidity."6 Wardrobe choices worked to differentiate the upper class from the underlings in Liberian society, poor African-Americans and the native African population. Some African-American arrivals in Liberia were shocked by what they viewed as some natives' lack of dress.7 Indigenous Africans, in turn, regarded settlers as "white." For them, whiteness was not about skin color but custom, such as clothing, writing, and religion.8 With such materialist definitions of civilization, clothing became an important marker of cultural difference.

The African assessment reinforced what settlers believed of themselves. They too shaped their identity around Western culture, commodities and social systems. Their new African context created the opportunity to dispose of a social hierarchy based on race, something considered innate, and shape their society on customs, something that can be aspired to or taught. Many settlers felt that their Western customs made them superior to their indigenous neighbors. Thus they reinstated, sometimes consciously and sometimes inadvertently, oppressive social hierarchies that echoed those they left behind in the United States.9 Perhaps in sending photographs from Africa, the photographer and sitters hoped that whites in America would recognize blacks' full human value and social equality when racial categories were subverted to a shared cultural framework.

These daguerreotypes were not only valuable for what they represented, but also for how they represented. The photographic medium itself had important cultural significance. By mid-century "to daguerreotype" meant to render an accurate depiction.10 Thus, photography was perhaps an ideal tool for colonization propaganda that claimed its authority based on reportage. Publication of first-hand accounts was one strategy colonizationists relied on to promote emigration to Liberia. Mass print media was an important tool of persuasion that preceded the advent of photography in 1839. Literacy among white Americans was high and, through newspapers, readers were able to engage with political and social issues debated in the public sphere. ACS rhetoric of proof found in print parallels the discourse of photographic "truth," making photography a useful tool to promote the enterprise.

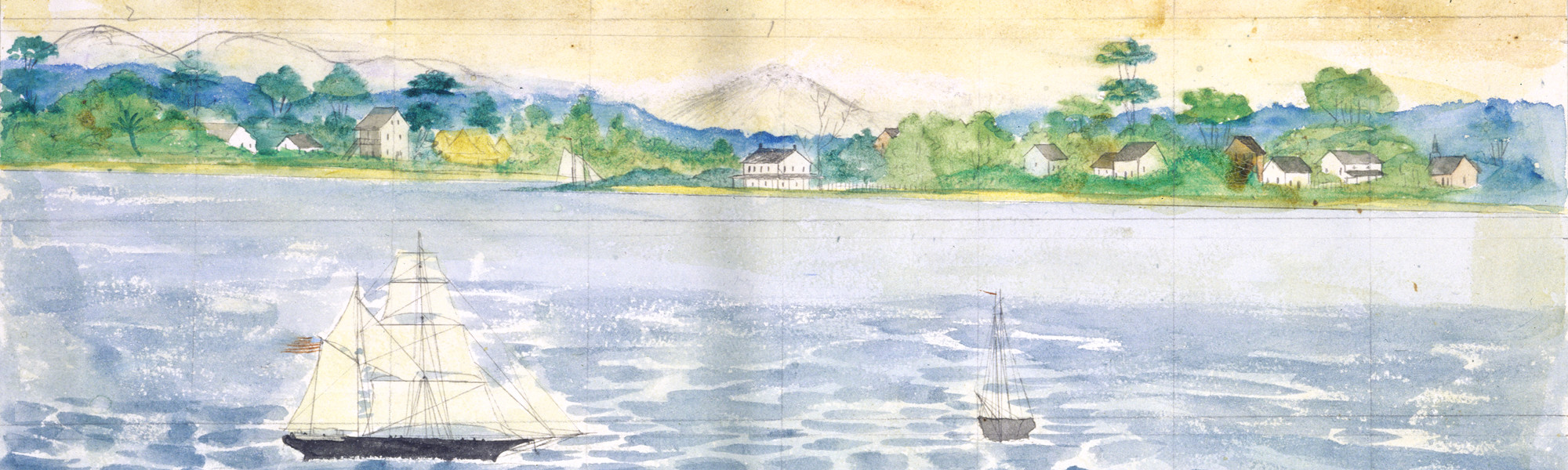

For authoritative claims to truth, colonization propaganda relied on travel journals by visitors to the settlement and letters from newly arrived immigrants to testify that Liberia was a thriving, healthful place. For example, ACS agent James W. Lugenbeel published "Sketches of Liberia," a written description of Liberia based on observations he made during his tenure as a colonial doctor in Monrovia. Lugenbeel stressed that his was not an historical account, but rather a transparent report of "utmost ingenuousness." His aim was to provide the unbiased reader with an "account of Liberia as it is."11 Similarly, the Pennsylvania Colonization Society commissioned a lithograph depicting their colony at Bassa Cove, Liberia. It was advertised as a print based on a drawing "made on the spot" by colonial agent Dr. Robert McDowall.12 Advertised as a faithful recording, the lithograph was available for sale for several years and was also used to decorate Pennsylvania Colonization Society membership certificates. Opponents of colonization also churned out their own eye-witness reports about Liberia which argued that colonizationists misrepresented the reality in Liberia. For example, William Nesbit's Four Months in Liberia contended that the land chosen by the ACS was unhealthy and the town settlements were dilapidated.13 These warring opinions pervaded the press coverage of Liberia for much of the century, from about 1820 to 1870.14

In this polemic debate about colonization, assertions such as "as it is" and "on the spot" point to a rhetoric about Liberia in mass print media that based claims to truth and legitimacy on direct observation and transparent representation of what had been seen. This rhetorical strategy resonates with the discourse about photography in the nineteenth century. Photographic discourse was rooted in positivism, where truth and knowledge could be acquired through observation.15 Photography was touted as transparent representation of reality based on mechanical and chemical technology that eliminated human intervention. The Society's reliance on truth claims based on eyewitness reportage may have led ACS agents to seek out the services of Augustus Washington who left the United States for Liberia with commissions for at least nine daguerreotypes from colonization supporters in at least four different states, including Philadelphia, New York, Connecticut, and Boston.16

Daguerreotypes, however, had their limitations. The portraits of Joseph and Jane Roberts were unique objects: silver-coated copper plates put under a glass cover and enclosed in elaborate cases. As singular objects, these photographs had limited circulation and the American Colonization Society needed images that could reach the larger American public. Realizing the need for some form of mass communication, New York colonizationist Rev. John B. Pinney wrote, "The spirit of the age demands the use of the press."17 The mid-nineteenth century experienced an explosion of popular print culture; printers churned out penny-press newspapers, ladies journals, and illustrated gift books. As editor of the New York Colonization Journal, a monthly paper published by the New York State Colonization Society, Pinney began integrating images into his publication within five years of beginning this newspaper.18

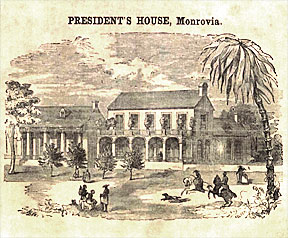

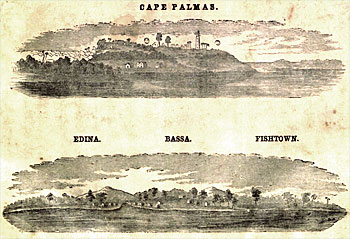

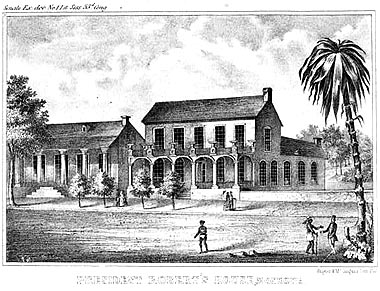

The addition of images to the New York Colonization Journal made an immediate impact on its readership and the New York auxiliary soon received requests from other state auxiliaries for use of its newspaper illustrations. "Orders came from all sections for it [the first illustrated issue], and among them 200 copies were sent to Richmond, VA," reported the Journal.19 Along with those requests was one from Virginia Colonization Society agent Reverend Philip Slaughter who used several woodcuts from the New York newspaper to illustrate his 1855 book The Virginian History of African Colonization.20 He used a wood-engraving representing Liberia's presidential mansion as the frontispiece for his book. Landscape views of other settler towns and a dramatization of President Robert's return from a trip abroad were placed at the end of the book. The images Slaughter appropriated from the New York Colonization Journal had themselves been borrowed from the National Magazine; Devoted to Literature, Art and Religion, which professed to be neutral on the slavery question. Such circulation, appropriation, and re-contextualization of imagery in colonization print media seems to follow a larger trend of cross-editing in nineteenth-century American newspapers, as editors routinely filled their columns with articles culled from other regional, national, international publications. What images remained in circulation, or fell from public view, and how they were recontextualized reflects how colonizationists wished to represent Liberia and what images resonated with their American audience. By using the presidential mansion as the frontispiece, Slaughter foregrounded the presidential mansion image over the other pictures that he borrowed from the Journal. A portrait of President Roberts, the lead illustration in the Journal and National Magazine, was altogether omitted. These editorial decisions offer clues to the ideological intentions behind the Virginian's aesthetic choices.

The picture of the presidential mansion represents Liberia with a grand home and genteel denizens. A large two-story home with a colonnaded porch faces a populated street. In the foreground, on the left, three bare-chested figures cluster in a silent triad. Viewers would have understood that these figures were African natives. On the right, a lady in a wide-brim hat rides sidesaddle on a white horse while a gentleman in a top hat and tail coats follows on his black horse. In the middle-ground, two couples take a walk down a tree-lined street. The entire picture is placed next to a view of Monrovia, implying that it is a close up detail of a larger landscape. The picture of the presidential mansion follows the pictorial conventions of nineteenth century house portraiture with which Virginians might have been familiar. However, the inclusion of African-Americans subverts the pictorial conventions of the genre in ways that reflect the racial discourse that informed written depictions of Liberian landscape and society.

Southerners may have been familiar with the landscape painting tradition of portraying large plantation homes.21 Paintings of grand homes were surrogate portraits of the owners. Virginia homes Mount Vernon and Monticello were frequent subject of paintings that carried with the representation of the home the hero worship of its owners, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson respectively. The picture of President Roberts' home follows the formula used to portray the homes of those prominent Virginians. The house is shown in three-fourths view, so as to capture the impressive length and depth of the edifice. As with portraits of people, portraits of homes were framed with accoutrements; like drapes framing a portrait, a palm tree acts as a repoussoir, or visual devise to "push the eye" back towards the presidential mansion. The palm was a signature element of colonization design used to portray Liberia as an idyllic, tropical landscape.22

While the presentation of Roberts' home conforms to the conventions of plantation paintings, the presence of African-American figures within the picture does not. Usually, if figures appear at all in such a composition, they are depictions of the white residents of the plantation engaged in leisure activities. Blacks are nearly invisible in these works since the slave labor that was the source of the plantation's prosperity was often omitted from the picture. African-Americans shown taking part in genteel pastimes may have enacted a sense of incongruity and racial inversion that underlies the racist caricature of cartoonist Edward Clay's series "Life in Philadelphia."23 On one hand, Clay's objective was to ridicule black aspirations to bourgeois dress and manners to highlight blacks' unabridgeable racial difference from and social inferiority to whites. On the other hand, the goal of the "presidential mansion" image was likely to show blacks effectively inhabiting roles and behavior typically attributed to whites. Yet, like Clay's work, this image relies on the cognitive dissonance between the perceived degraded status of blacks in the United States and the elegance and pageantry of the activities depicted in the wood engraving in order to convey how improved blacks' social station could be in Liberia. The pairing of black and white horses literalize (or should I say visualize) the play on notions of racial contrast and inversion.24

The placement of the African natives also highlights the social position of the African American settlers in Liberian society. Natives and settlers stand isolated from one another on islands of whiteness separated by a chasm of black hatching, suggesting the marginalization of the native in Liberian society.25 For an American audience, this spatial and social distinction also emphasized the difference between being African and African-American. The juxtaposition of native and settler highlights the cultural similarity of African-American settlers in Liberia to Euro-Americans in the United States. In The Virginia History of African Colonization, Slaughter argued that divine providence brought Africans into slavery and through slavery blacks were elevated into a state of civilization, "far above his race in his native seat."26 This belief in the evolutionary growth of African-Americans through exposure to Western culture may have informed his understanding of the representation of difference between settler and native in the illustration.

Comparison of Slaughter's illustration to an earlier 1853 rendition of the image published as a lithograph in U.S. Navy Commodore W. F. Lynch's official report of a mission to Africa for the U.S. Senate demonstrates the degree to which the image had been manipulated to draw out its message of refinement and civilization. For example, the cornices of the balusters on the second story balcony of the mansion were turned into planters for manicured hedges. The figural groups in the foreground are also different. In the senate report, a man in native dress and one in western clothes face one another in mirrored poses suggesting communication and commonality. The racial identity of the westerner is unclear—perhaps he is European or simply a figure rendered in white to provide contrast against the grey background. Either way, the pairing of the (clothed and civilized) "white" man with the (unclothed and uncivilized) black native stages a racial and cultural duality. The contrasting white and black horses in subsequent renditions of the image rearticulated the tensions of sameness and difference played out in this figural group to portray Liberian identity for an audience that may have seen African-American's as a racial other. Together these alterations reorganize the social space of the mansion from one of communication and mutual exchange to one of separation and social hierarchy—changes that happened before Slaughter found the image but he nonetheless perpetuated by reprinting the image.

To scholars of nineteenth-century Liberia, the scene is hardly factual. Horses were rare in the settlement because beasts of burden were susceptible to diseases found on the West African coast.27 The presidential mansion and its surrounds may not have been as grand as it is depicted here. Indeed, other landscapes at the back of Reverend Slaughter's book presented Liberia as fledgling settlements of modest dwellings surrounded by foliage. One might also observe the disparity between this illustration and a photograph of the same street several decades later. Dirt roads and modest building materials suggest a much more humble presidential residence. (It should be noted that photographs are also artificial constructions: position, framing, and perspective are all chosen to forward overt or implicit ideological goals.) Opponents might have challenged the validity of this image, though no alternate visual representations appear to have been made. "The meanest village that I know in the United States, far transcends Monrovia in the beauty of its buildings, and the appearance of its thrift," wrote William Nesbit.28 For colonizationists, however, the inclusion of the equestrian vignette and Italianate architecture serve as a visual simile, following accounts that blacks in Liberia could achieve the social and political stature of whites in the United States and that Monrovia was in fact beginning to look like small towns in America. Slaughter could have provided his own defense of his editorial decision to use this image when he wrote that: "Colonists have been charged with painting too flattering portraits of this young republic. We admit that this has sometimes been done. Exaggeration is the child of enthusiasm, as enthusiasm is generally the parent of novel and bold enterprises."29

These examples of colonization pictures demonstrate that visual imagery can enrich our understanding of the propaganda strategies and cultural underpinnings of the American Colonization Society. The Society employed visual media that would reinforce their propaganda strategies. The contemporary discourse of photography suggests that daguerreotypes would be understood not only as pictures but visual proof to verify colonizationists claims. By harnessing the power of the press, colonizationists were able to reach a wider audience with wood engraved illustrations that not only embellished newspapers but also constructed visual messages of their own. Although both photograph and print were commissioned with the common goal of promoting African colonization, they differ in how they draw on notions of race, slavery, and civilization to represent the African-American settler. By sitting for their portrait, the Robertses were active participants in the portrait making process, co-creators of imagery intended to convince viewers of the African-American dignity in Liberia by marshalling dress and pose as signifiers of civilization and bourgeois respectability. Slaughter's use of the picture of the Robertses' home, however, relies on racial contrast and inversion to depict a black republic as civilized and genteel for an audience that saw such attributes as authentically white. These observations move away from using colonization pictures as illustrations to accompany text-based historical analysis and toward employing them as primary documents that further our understanding of how Liberia was represented for a public faced with debates over race and slavery in antebellum America.